Projekt Löcher stopfen

Materials:

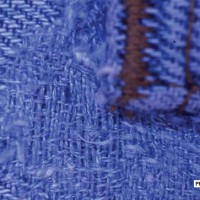

Wool, thread, darning mushrooms, needles, receipt books, logo stamp, signage, video, voice recordings, work tables, projection, video screens, embroidery hoops and magnifying glasses.

Concept:

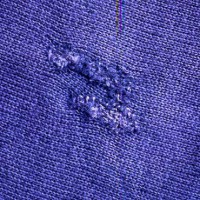

The project was called ‘Löcher Stopfen’, which in English means darning-holes. The multiple stages of the project all maintained this central theme: Darning offered as a service in exchange for a story.

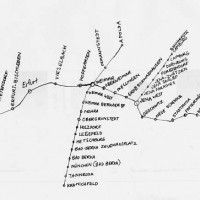

The research location was Thuringia in central Germany. The epicentre was in Weimar (a city of approximately sixty-three thousand people) where founding discussions that initiated the series of actions began. The artists worked nomadically following stories from one place to another, carrying in a backpack the tools of the trade, which consisted of a small sewing box filled with fine yarns, needles, clippers, a darning mushroom, plus a still and a video camera and portable tripod. Travel was only limited by the extent of the urban transport network. The interviews all took place within a three-hundred kilometre radius from Weimar, including outer suburbs of Berlin, Schmölln, Bad Berka and many more. Participants helped connect the artist to the next story, like following Chinese whispers a web of networks emerged. In the initial phase the interviews took place in the private homes of participants. Participants provided the object to be darned. The artist recorded the hole being filled while the story was being told. A receipt was issued for the exchange and a photograph was taken to document the darn patch.

The second phase was a series of workshops in the small village of Schmölln. Fifty participants learnt or shared darning techniques while participating in an open discussion on the theme.

The third phase functioned as a small business, working from a kiosk in Weimar for a month. The kiosk was packed full of coloured wools and darning supplies. The artist advertised for donations and the kiosk was quickly filled. The windows of the kiosk advertised the service declaring to the busy intersection: “Have you got a Hole. We can Help. Free Service”, with a telephone number to call. The service was also advertised in the newspaper and was quickly booked out. The artist and participant sat quietly working and storytelling inside the confines of the glass box, isolated but on display to the bustle of the city. ‘Like an archive Flanagan collected and stored both the pictures of the mended holes and the related recordings of the stories which, in the end, filled them – text became textile and vice versa.’13

Text and textile are etymologically linked. “‘Text’ in Latin is ‘textus’ (u-stem) style, tissue of a literary work (Quintilian), lit. that which is woven, web, texture, f. text-, ppl. Stem of tex-e re to weave. The wording of anything written or printed; the structure formed by the words in their order; the very words, phrases and sentences as written.”14 Kathryn Sullivan Kruger’s research suggests that historically story telling and weaving were originally analogous acts.15 ‘A textile is a tissue. Made up of a string of letters like DNA it can be read as a text, understood as a form, seen as a body. The moment we translate any thought into words it forms a text. The translation of thought into words is potent with the cultural meaning inherent in the language in which it is spoken. The environment can be understood as text and through every translation it evolves.’16

At the end of the project a selection of the video recordings made throughout the process were shown in an interactive installation in a theatre inside the railway station in Weimar. The installation consisted of two large worktables, each with a horizontal screen in the centre. Looking down on the tabletop put the viewer in the position of looking down over the textile being darned watching the hands stitching and the hole filling whilst hearing the story told by the owner of the garment. Around the edges of the table, the actual garments with their darn patch displayed in embroidery hoops were suspended a foot above the surface of the table top, angled to maximise display or as though the embroiderer had finished darning and left the room. The lighting was low to maximize the audiovisuals, so each embroidery hoop had its own self-lit magnifying glass to enable the viewer to inspect the work in detail. Away from this pre-industrial factory scene of the worktables, another low large plinth displayed an assortment of collected darning mushrooms, on old sewing box and yarns. The plinth was a suitable height to sit around the edges and was sharply lit by a spotlight, enabling the visitor to try the fine work for him or herself. On the wall behind this workspace, was projected the magnified images of finely woven darning samples, created by workshop participants as well as by the artist.

Meanwhile outside the exhibition five buskers were darning, like shoe shiners, they were posted around the railway station, with a sign advertising their service, and the exhibition. This time the stories were to be written by the participant in receipt books provided. Invitations to the exhibition had informed guests that this service would be available, so the darners were kept busy all day, but a review of the receipt books revealed the action had attracted and involved many passing travellers as well as invited guests.

‘Clothing and accessories have always served as a membrane between the outside public world and the inside private world of our body.’17

“Etymologically ‘darn, dern, dearn means to ‘hide, conceal and keep a secret. A source sited in the Oxford English Dictionary dates as early as c.893 (spelt in Old English dyrnan). The verb used to describe a form of repair. Darn dern, dearn … ‘…appears about 1600, and becomes at once quite common: it may be that this particular way of repairing a hole or rent was then introduced. The form suggests a relationship to DERN (later darn) secret, hidden, and its verb dern, darn to conceal, put out of sight; but satisfactory connecting links between the two have not been found yet.’18

The action of darning and storytelling could be seen as revealing and concealing simultaneously. To discuss a memory is to reveal personal thoughts, bring them to life. To repair a site attempts to hide the evidence. But a darn is never really hidden, its beauty is in the attempt to clone its host; it adds another layer of meaning.”19

Throughout the different phases of the project darning acted as a catalyst for discussions on many different levels, ranging from personal stories, anecdotes and memories, to philosophy, economics and politics.

To contextualise the action briefly: After the Bauhaus was forced to leave Weimar in 1925 there was no further development in international modern art. The Nazis came into power in the thirties, followed by the Russian occupation after World War II. Abstract art was banned in 1951 in the GDR (German Democratic Republic) as a result of the “formalism debate” social realism became the state sanctioned form of art.

Professor Liz Bachubber wrote, about the work: ‘The strength of project Löcher Stopfen is that it is highly communicative involving citizens in all walks of life in a process that allowed them to reflect upon their society and culture. They learned to see their personal histories in the former GDR in a new way – not as a failed political and social system but rather, as a culture of innovative do-it-yourself crafts people who, with found or traded materials, helped to preserve and recycle in the best ecological way. The works interactive processes instilled a positive sense of identity in this microcosm of former East German society, which still suffer from a sense of lost identity. The thesis work, in short, pays homage to non-consumerist society and sustainable development in daily life.’20

Darning can be mastered in an hour, it is cheap and portable and effectively transfers power from the hands of the mass producer to the individual. To create the weft oneself and to repair a broken structure embodies autonomy. An individual action functions as a visual symbol, displayed emblematically on the consumer object. This work does not promote antiglobalism or anti-capitalism but simply encourages an awareness of ground level responsibility for our actions.

Exhibitions:

‘The Wearable Art Show’, Tighes Hill Gallery, Tighes Hill, Australia, 2005.

D.A.S. Jugendtheater Stellwerk e.V. in Weimar Railway Station, February 2004.

K and K Kiosk, Weimar, Germany, January 2004.

Publications:

HOHMANN, K. & TIETZE, K. (2006) Flicken. IN HOHMANN, K. & TIETZE, K. (Eds.) K & K. Magazin. Weimar, Bauhaus-Universität Publishers. Pp. 3, 102 – 3.

STOWELL, J. (2005) From the Young at Art. The Newcastle Herald. 12th Mar. ed. Newcastle. P. 14.

STOWELL, J. (2005) Around the Galleries. The Newcastle Herald. 5th Mar. ed. Newcastle. P. 10.

SCANLAN, R. (2004) A Darn Good Story. CETUS, Oct.. P. 12.

SCANLAN, R. (2004) Darning her way to Success. Uni News. P. 1.

FLANAGAN, T. (2004) Public Art and Alternative Tactics in a Post Acquisitive Society. Faculty of Art and Design Weimar, Bauhaus University.

(2004) Für die Australien Tricia Flanagan. Thuringia Landeszeitung. 3rd Feb. ed. Weimar. P. 2.

WENSEL, H. (2004) “Ich Sammle Löcher” Weimarer Allgemeine. 12th Jan. ed. Weimar, Germany. P. 1.

(2004) Kunstaktion mit Tricia Flanagan. Thuringia Landeszeitung. 6th Jan. ed. Weimar, Germany. P. 2.

Endnotes:

13. HOHMANN, K. & TIETZE, K. (2004) Flicken. Weimar, K & K Zentrum für Kunst Appendix Endnotes 311 und Mode. P. 103.

14. “Oxford English Dictionary”, second edition, 1997, CD Rom version 2.0, Oxford University Press, 1997.

15. HEMMINGS, J. (2003) Book Reviews – ‘Weaving the Word: The Metaphorics of Weaving and Female Textual Production’ (Selingsgrove: Susquehanna University Press and London: Associated University Press, 2001) by Kathryn Sullivan Kruger and ‘Architecture and the Text: The (S) crypts of Joyce and Piranesi’ (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993) by Jennifer Bloomer. Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture, Volume 1, Number 1, 1 March 2003, pp. 106-108(3), Publisher: Berg Publishers, Vol 1, 3.

16. FLANAGAN, T. (2004) Public Art and Alternative Tactics in Post-Acquisitive Society. Facultät Gestaltung. Weimar, Bauhaus University Weimar, Germany. P. 15.

17. ANDERSON, K. & BERZOWSKA, J. (2006) Worn Technology – The Alteration of Social Space. IN SEIJDEL, J. (Ed.) Hybrid space : how wireless media mobilize public space. Rotterdam, NAi Publishers. P. 148.

18. “Oxford English Dictionary”, second edition, 1997, CD Rom version 2.0, Oxford University Press, 1997.

19. FLANAGAN, T. (2004) Public Art and Alternative Tactics in Post-Acquisitive Society. Facultät Gestaltung. Weimar, Bauhaus University Weimar, Germany. P. 12.

20. BACHHUBER, L. (2003) personal correspondence. IN FLANAGAN, T. (Ed. Weimar.

Thanks:

- Prof. Liz Bachubber

- Prof. phil. Habil. Lorenz Engell

- Christain Hasucha

- Peter Benz

- Nicole Degenhardt

- Sabine Eichilz

- Renate Enke

- Cornelia Erdmann

- Evren Erildiz

- Benjamin Flanagan

- Sheree Fleming

- Esther Glück

- Götz Greiner

- Stefan Häfner

- Steffen Hagemann

- Christiana Hasse

- Michael Hesse

- Chris Hoff

- Katherina Hohmann

- Julia Horezky

- Andrea Huhndorf

- Louise Kammerer

- Kai Kemmann

- Herr Koon

- Stephen Klee

- Verena Kyselka

- Nina Lundström

- Teresa Luzio

- Bianca Mancini

- Ayumi Matsuzaka

- James Mc Donald

- Silke Opitz

- Andrew Piggott

- Christoph and Leonie Rihs

- Jirka Reichmann

- Reiner Reisner

- Felix Ruffert

- Prof. Dr. Phil. Habil. Karl Schawelka

- Daniel Schmidt

- Ingeburg and Jan Sedlacek

- Brita Sepka

- Kai Sinzinger

- Günter Spitze

- Katherina Tietze

- Manuela Ulbrich

- Leonie Weber